Safety of Nuclear Power Reactors

(Updated March 2022)

- From the outset, there has been a strong awareness of the potential hazard of both nuclear criticality and release of radioactive materials from generating electricity with nuclear power.

- As in other industries, the design and operation of nuclear power plants aims to minimise the likelihood of accidents, and avoid major human consequences when they occur.

- There have been two major reactor accidents in the history of civil nuclear power – Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi. Chernobyl involved an intense fire without provision for containment, and Fukushima Daiichi severely tested the containment, allowing some release of radioactivity.

- These are the only major accidents to have occurred in over 18,500 cumulative reactor-years of commercial nuclear power operation in 36 countries.

- The evidence over six decades shows that nuclear power is a safe means of generating electricity. The risk of accidents in nuclear power plants is low and declining. The consequences of an accident or terrorist attack are minimal compared with other commonly accepted risks. Radiological effects on people of any radioactive releases can be avoided.

Context

In relation to nuclear power, safety is closely linked with security, and in the nuclear field also with safeguards. Some distinctions apply:

- Safety focuses on unintended conditions or events leading to radiological releases from authorised activities. It relates mainly to intrinsic problems or hazards.

- Security focuses on the intentional misuse of nuclear or other radioactive materials by non-state elements to cause harm. It relates mainly to external threats to materials or facilities (ee information page on Security of Nuclear Facilities and Material).

- Safeguarding focuses on restraining activities by states that could lead to acquisition or development of nuclear weapons. It concerns mainly materials and equipment in relation to rogue governments (see information page on Safeguards to Prevent Nuclear Proliferation).

No industry is immune from accidents, but all industries learn from them. In civil aviation, there are accidents every year and each is meticulously analysed. The lessons from nearly one hundred years’ experience mean that reputable airlines are extremely safe. In the chemical industry and oil-gas industry, major accidents also lead to improved safety. There is wide public acceptance that the risks associated with these industries are an acceptable trade-off for our dependence on their products and services. With nuclear power, the high energy density makes the potential hazard obvious, and this has always been factored into the design of nuclear power plants. The few accidents have been spectacular and newsworthy, but of little consequence in terms of human fatalities. The novelty value and hence newsworthiness of nuclear power accidents remains high in contrast with other industrial accidents, which receive comparatively little news coverage.

Harnessing the world's most concentrated energy source

In the 1950s attention turned to harnessing the power of the atom in a controlled way, as demonstrated at Chicago in 1942 and subsequently for military research, and applying the steady heat yield to generate electricity. This naturally gave rise to concerns about accidents and their possible effects. However, with nuclear power, safety depends on much the same factors as in any comparable industry: intelligent planning, proper design with conservative margins and back-up systems, high-quality components and a well-developed safety culture in operations. The operating lives of reactors depend on maintaining their safety margin.

A particular nuclear scenario was loss of cooling which resulted in melting of the nuclear reactor core, and this motivated studies on both the physical and chemical possibilities as well as the biological effects of any dispersed radioactivity. Those responsible for nuclear power technology in the West devoted extraordinary effort to ensuring that a meltdown of the reactor core would not take place, since it was assumed that a meltdown of the core would create a major public hazard, and if uncontained, a tragic accident with likely multiple fatalities.

In avoiding such accidents the industry has been very successful. In the 60-year history of civil nuclear power generation, with over 18,500 cumulative reactor-years across 36 countries, there have been only three significant accidents at nuclear power plants:

- Three Mile Island (USA 1979) where the reactor was severely damaged but radiation was contained and there were no adverse health or environmental consequences.

- Chernobyl (Ukraine 1986) where the destruction of the reactor by steam explosion and fire killed two people initially plus a further 28 from radiation poisoning within three months, and had significant health and environmental consequences.

- Fukushima Daiichi (Japan 2011) where three old reactors (together with a fourth) were written off after the effects of loss of cooling due to a huge tsunami were inadequately contained. There were no deaths or serious injuries due to radioactivity, though about 19,500 people were killed by the tsunami.

Of all the accidents and incidents, only the Chernobyl and Fukushima accidents resulted in radiation doses to the public greater than those resulting from the exposure to natural sources. The Fukushima accident resulted in some radiation exposure of workers at the plant, but not such as to threaten their health, unlike Chernobyl. Other incidents (and one 'accident') have been completely confined to the plant.

Apart from Chernobyl, no nuclear workers or members of the public have ever died as a result of exposure to radiation due to a commercial nuclear reactor incident. Most of the serious radiological injuries and deaths that occur each year (2-4 deaths and many more exposures above regulatory limits) are the result of large uncontrolled radiation sources, such as abandoned medical or industrial equipment. (There have also been a number of accidents in experimental reactors and in one military plutonium-producing pile – at Windscale, UK, in 1957 – but none of these resulted in loss of life outside the actual plant, or long-term environmental contamination.) See also Table in Appendix 2: Serious Nuclear Reactor Accidents.

It should be emphasised that a commercial-type power reactor simply cannot under any circumstances explode like a nuclear bomb – the fuel is not enriched beyond about 5%, and much higher enrichment is needed for explosives.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was set up by the United Nations in 1957. One of its functions was to act as an auditor of world nuclear safety, and this role was increased greatly following the Chernobyl accident. It prescribes safety procedures and the reporting of even minor incidents. Its role has been strengthened since 1996 (see later section). Every country which operates nuclear power plants has a nuclear safety inspectorate and all of these work closely with the IAEA.

While nuclear power plants are designed to be safe in their operation and safe in the event of any malfunction or accident, no industrial activity can be represented as entirely risk-free. Incidents and accidents may happen, and as in other industries, what is learned will lead to a progressive improvement in safety. Those improvements are both in new designs, and in upgrading of existing plants. The long-term operation (LTO) of established plants is achieved by significant investment in such upgrading.

The safety of operating staff is a prime concern in nuclear plants. Radiation exposure is minimised by the use of remote handling equipment for many operations in the core of the reactor. Other controls include physical shielding and limiting the time workers spend in areas with significant radiation levels. These are supported by continuous monitoring of individual doses and of the work environment to ensure very low radiation exposure compared with other industries.

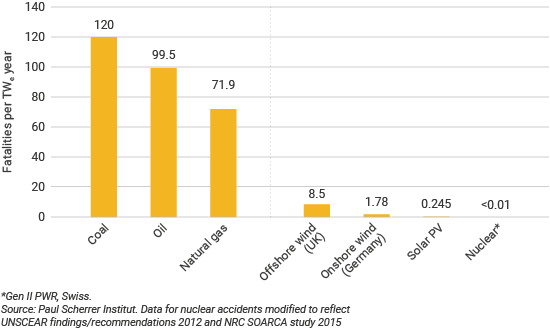

The use of nuclear energy for electricity generation can be considered extremely safe. Every year several hundred people die in coal mines to provide this widely used fuel for electricity. There are also significant health and environmental effects arising from fossil fuel use. Contrary to popular belief, nuclear power saves lives by displacing fossil fuel from the electricity mix.

Achieving safety: the reactor core

Concerning possible accidents, up to the early 1970s, some extreme assumptions were made about the possible chain of consequences. These gave rise to a genre of dramatic fiction (e.g. The China Syndrome) in the public domain and also some solid conservative engineering including containment structures in the industry itself. Licensing regulations were framed accordingly.

It was not until the late 1970s that detailed analyses and large-scale testing, followed by the 1979 meltdown of the Three Mile Island reactor, began to make clear that even the worst possible accident in a conventional western nuclear power plant or its fuel would not be likely to cause dramatic public harm. The industry still works hard to minimize the probability of a meltdown accident, but it is now clear that no-one need fear a potential public health catastrophe simply because a fuel meltdown happens. Fukushima Daiichi has made that clear, with a triple meltdown causing no fatalities or serious radiation doses to anyone, while over two hundred people continued working onsite to mitigate the accident's effects.

The decades-long test and analysis programme showed that less radioactivity escapes from molten fuel than initially assumed, and that most of this radioactive material is not readily mobilized beyond the immediate internal structure. Thus, even if the containment structure that surrounds all modern nuclear plants were ruptured, as was the case with one of the Fukushima reactors, it is still very effective in preventing the escape of most radioactivity.

A mandated safety indicator is the calculated probable frequency of degraded core or core melt accidents. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) specifies that reactor designs must meet a theoretical 1 in 10,000 year core damage frequency, but modern designs exceed this. US utility requirements are 1 in 100,000 years, the best currently operating plants are about 1 in one million and those likely to be built in the next decade are almost 1 in 10 million. While this calculated core damage frequency has been one of the main metrics to assess reactor safety, European safety authorities prefer a deterministic approach, focusing on actual provision of back-up hardware, though they also undertake probabilistic safety analysis (PSA) for core damage frequency, and require a 1 in 1 million core damage frequency for new designs.

Even months after the Three Mile Island (TMI) accident in 1979 it was assumed that there had been no core melt because there were no indications of severe radioactive release even inside the containment. It turned out that in fact about half the core had melted. Until 2011 this remained the only core melt in a reactor conforming to NRC safety criteria, and the effects were contained as designed, without radiological harm to anyone.* Greifswald 5 in East Germany had a partial core melt in November 1989, due to malfunctioning valves (root cause: shoddy manufacture) and was never restarted. At Fukushima in 2011 (a different reactor design with penetrations in the bottom of the pressure vessel) the three reactor cores evidently largely melted in the first two or three days, but this was not confirmed for about ten weeks. It is still not certain how much of the core material was not contained by the pressure vessels and ended up in the bottom of the drywell containments, though certainly there was considerable release of radionuclides to the atmosphere early on, and later to cooling water**.

* About this time there was alarmist talk of the so-called 'China Syndrome', a scenario where the core of such a reactor would melt, and due to continual heat generation, melt its way through the reactor pressure vessel and concrete foundations to keep going, perhaps until it reached China on the other side of the globe! The TMI accident proved the extent of truth in the proposition, and the molten core material got exactly 15 mm of the way to China as it froze on the bottom of the reactor pressure vessel.

** Ignoring isotopic differences, there are about one hundred different fission products in fuel which has been undergoing fission. A few of these are gases at normal temperatures, more are volatile at higher temperatures, and both will be released from the fuel if the cladding is damaged. The latter include iodine (easily volatilised, at 184°C) and caesium (671°C), which were the main radionuclides released at Fukushima, first into the reactor pressure vessel and then into the containment which in unit 2 apparently ruptured early on day 5. In addition, as cooling water was flushed through the hot core, soluble fission products such as caesium dissolved in it, which created the need for a large water treatment plant to remove them.

Apart from these accidents and the Chernobyl disaster there have been about ten core melt accidents – mostly in military or experimental reactors – Appendix 2 lists most of them. None resulted in any hazard outside the plant from the core melting, though in one case there was significant radiation release due to burning fuel in hot graphite (similar to Chernobyl but smaller scale). The Fukushima accident should also be considered in that context, since the fuel was badly damaged and there were significant off-site radiation releases.

Licensing approval for new plants today requires that the effects of any core-melt accident must be confined to the plant itself, without the need to evacuate nearby residents.

The main safety concern has always been the possibility of an uncontrolled release of radioactive material, leading to contamination and consequent radiation exposure off-site. Earlier assumptions were that this would be likely in the event of a major loss of cooling accident (LOCA) which resulted in a core melt. The TMI experience suggested otherwise, but at Fukushima this is exactly what happened. In the light of better understanding of the physics and chemistry of material in a reactor core under extreme conditions it became evident that even a severe core melt coupled with breach of containment would be unlikely to create a major radiological disaster from many Western reactor designs, but the Fukushima accident showed that this did not apply to all. Studies of the post-accident situation at TMI (where there was no breach of containment) supported the suggestion, and analysis of Fukushima will be incomplete until the reactors are dismantled.

Certainly the matter was severely tested with three reactors of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan in March 2011. Cooling was lost about an hour after a shutdown, and it proved impossible to restore it sufficiently to prevent severe damage to the fuel. The reactors, dating from 1971-75, were written off. A fourth is also written off due to damage from a hydrogen explosion.

Achieving optimum nuclear safety

A fundamental principle of nuclear power plant operation worldwide is that the operator is responsible for safety. The national regulator is responsible for ensuring the plants are operated safely by the licensee, and that the design is approved. A second important concept is that a regulator’s mission is to protect people and the environment.

Design certification of reactors is also the responsibility of national regulators. There is international collaboration among these to varying degrees, and there are a number of sets of mechanical codes and standards related to quality and safety.

With new reactor designs being established on a more international basis since the 1990s, both the industry and regulators are seeking greater design standardization and also regulatory harmonization. The role of the World Nuclear Association's Cooperation in Reactor Design Evaluation and Licensing (CORDEL) Working Group and the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency's (NEA's) Multinational Design Evaluation Programme (MDEP) are described in the information page on Cooperation in Nuclear Power.

An OECD-NEA report in 2010 pointed out that the theoretically-calculated frequency for a large release of radioactivity from a severe nuclear power plant accident has reduced by a factor of 1600 between the early Generation I reactors as originally built and the Generation III/III+ plants being built today. Earlier designs however have been progressively upgraded through their operating lives.

It has long been asserted that nuclear reactor accidents are the epitome of low-probability but high-consequence risks. Understandably, with this in mind, some people were disinclined to accept the risk, however low the probability. However, the physics and chemistry of a reactor core, coupled with but not wholly depending on the engineering, mean that the consequences of an accident are likely in fact be much less severe than those from other industrial and energy sources. Experience, including Fukushima, bears this out.

A 2009 US Department of Energy (DOE) Human Performance Handbook notes: "The aviation industry, medical industry, commercial nuclear power industry, US Navy, DOE and its contractors, and other high-risk, technologically complex organizations have adopted human performance principles, concepts, and practices to consciously reduce human error and bolster controls in order to reduce accidents and events... About 80% of all events are attributed to human error. In some industries, this number is closer to 90%. Roughly 20% of events involve equipment failures. When the 80% human error is broken down further, it reveals that the majority of errors associated with events stem from latent organizational weaknesses (perpetrated by humans in the past that lie dormant in the system), whereas about 30% are caused by the individual worker touching the equipment and systems in the facility. Clearly, focusing efforts on reducing human error will reduce the likelihood of events." Following the Fukushima accident the focus has been on the organizational weaknesses which increase the likelihood of human error.

Defence-in-depth

To achieve optimum safety, nuclear plants in the western world operate using a 'defence-in-depth' approach, with multiple safety systems supplementing the natural features of the reactor core. Key aspects of the approach are:

- High-quality design & construction.

- Equipment which prevents operational disturbances or human failures and errors developing into problems.

- Comprehensive monitoring and regular testing to detect equipment or operator failures.

- Redundant and diverse systems to control damage to the fuel and prevent significant radioactive releases.

- Provision to confine the effects of severe fuel damage (or any other problem) to the plant itself.

These can be summed up as: prevention, monitoring, and action (to mitigate consequences of failures).

The safety provisions include a series of physical barriers between the radioactive reactor core and the environment, the provision of multiple safety systems, each with backup and designed to accommodate human error. As well as the physical aspects of safety, there are institutional aspects which are no less important – see following section on International Collaboration.

The barriers in a typical plant are: the fuel is in the form of solid ceramic (UO2) pellets, and radioactive fission products remain largely bound inside these pellets as the fuel is burned. The pellets are packed inside sealed zirconium alloy tubes to form fuel rods. These are confined inside a large steel pressure vessel with walls up to 30 cm thick – the associated primary water cooling pipework is also substantial. All this, in turn, is enclosed inside a robust reinforced concrete containment structure with walls at least one metre thick. This amounts to three significant barriers around the fuel, which itself is stable up to very high temperatures.

These barriers are monitored continually. The fuel cladding is monitored by measuring the amount of radioactivity in the cooling water. The high pressure cooling system is monitored by the leak rate of water, and the containment structure by periodically measuring the leak rate of air at about five times atmospheric pressure.

Looked at functionally, the three basic safety functions in a nuclear reactor are:

- To control reactivity.

- To cool the fuel.

- To contain radioactive substances.

The main safety features of most reactors are inherent – negative temperature coefficient and negative void coefficient. The first means that beyond an optimal level, as the temperature increases the efficiency of the reaction decreases (this in fact is used to control power levels in some new designs). The second means that if any steam has formed in the cooling water there is a decrease in moderating effect so that fewer neutrons are able to cause fission and the reaction slows down automatically.

In the 1950s and 1960s some experimental reactors in Idaho were deliberately tested to destruction to verify that large reactivity excursions were self-limiting and would automatically shut down the fission reaction. These tests verified that this was the case.

Beyond the control rods which are inserted to absorb neutrons and regulate the fission process, the main engineered safety provisions are the back-up emergency core cooling system (ECCS) to remove excess heat (though it is more to prevent damage to the plant than for public safety) and the containment.

Traditional reactor safety systems are 'active' in the sense that they involve electrical or mechanical operation on command. Some engineered systems operate passively, e.g. pressure relief valves. Both require parallel redundant systems. Inherent or full passive safety design depends only on physical phenomena such as convection, gravity or resistance to high temperatures, not on functioning of engineered components. All reactors have some elements of inherent safety as mentioned above, but in some recent designs the passive or inherent features substitute for active systems in cooling etc. Such a design would have averted the Fukushima accident, where loss of electrical power resulted is loss of cooling function.

The basis of design assumes a threat where due to accident or malign intent (e.g. terrorism) there is core melting and a breach of containment. This double possibility has been well studied and provides the basis of exclusion zones and contingency plans. Apparently during the Cold War neither Russia nor the USA targeted the other's nuclear power plants because the likely damage would be modest.

Nuclear power plants are designed with sensors to shut them down automatically in an earthquake, and this is a vital consideration in many parts of the world. (See Nuclear Power Plants and Earthquakes paper)

Severe accident management

In addition to engineering and procedures which reduce the risk and severity of accidents, all plants have guidelines for severe accident management or mitigation (SAM). These conspicuously came into play after the Fukushima accident, where staff had immense challenges in the absence of power and with disabled cooling systems following damage done by the tsunami. The experience following that accident is being applied not only in design but also in such guidelines, and peer reviews on nuclear plants are focusing more on these than previously.

In mid-2011 the IAEA Incident and Emergency Centre launched a new secure web-based communications platform to unify and simplify information exchange during nuclear or radiological emergencies. The Unified System for Information Exchange on Incidents and Emergencies (USIE) has been under development since 2009 but was actually launched during the emergency response to the accident at Fukushima.

In both the TMI and Fukushima accidents the problems started after the reactors were shut down – immediately at TMI and after an hour at Fukushima, when the tsunami arrived. The need to remove decay heat from the fuel was not met in each case, so core melting started to occur within a few hours. Cooling requires water circulation and an external heat sink. If pumps cannot run due to lack of power, gravity must be relied upon, but this will not get water into a pressurised system – either reactor pressure vessel or containment. Hence there is provision for relieving pressure, sometimes with a vent system, but this must work and be controlled without power. There is a question of filters or scrubbers in the vent system: these need to be such that they do not block due to solids being carried. Ideally any vent system should deal with any large amounts of hydrogen, as at Fukushima, and have minimum potential to spread radioactivity outside the plant. Filtered containment ventilation systems (FCVSs) have been retrofitted to some reactors which did not already have them, or any of sufficient capacity, following the Fukushima accident. The basic premise of a FCVS is that, independent of the state of the reactor itself, the catastrophic failure of the containment structure can be avoided by discharging steam, air and incondensable gases like hydrogen to the atmosphere.

The Three Mile Island accident in 1979 demonstrated the importance of the inherent safety features. Despite the fact that about half of the reactor core melted, radionuclides released from the melted fuel mostly plated out on the inside of the plant or dissolved in condensing steam. The containment building which housed the reactor further prevented any significant release of radioactivity. The accident was attributed to mechanical failure and operator confusion. The reactor's other protection systems also functioned as designed. The emergency core cooling system would have prevented any damage to the reactor but for the intervention of the operators.

Investigations following the accident led to a new focus on the human factors in nuclear safety. No major design changes were called for in western reactors, but controls and instrumentation were improved significantly and operator training was overhauled.

At Fukushima Daiichi in March 2011 the three operating reactors shut down automatically, and were being cooled as designed by the normal residual heat removal system using power from the back-up generators, until the tsunami swamped them an hour later. The emergency core cooling systems then failed. Days later, a separate problem emerged as spent fuel ponds lost water. Analysis of the accident showed the need for more intelligent siting criteria than those used in the 1960s, and the need for better back-up power and post-shutdown cooling, as well as provision for venting the containment of that kind of reactor and other emergency management procedures.

Nuclear plants have Severe Accident Mitigation Guidelines (SAMG, or in Japan: SAG), and most of these, including all those in the USA, address what should be done for accidents beyond design basis, and where several systems may be disabled. See section below.

In 2007 the US NRC launched a research program to assess the possible consequences of a serious reactor accident. Its draft report was released nearly a year after the Fukushima accident had partly confirmed its findings. The State-of-the-Art Reactor Consequences Analysis (SOARCA) showed that a severe accident at a US nuclear power plant (PWR or BWR) would not be likely to cause any immediate deaths, and the risks of fatal cancers would be vastly less than the general risks of cancer. SOARCA's main conclusions fall into three areas: how a reactor accident progresses; how existing systems and emergency measures can affect an accident's outcome; and how an accident would affect the public's health. The principal conclusion is that existing resources and procedures can stop an accident, slow it down or reduce its impact before it can affect the public, but even if accidents proceed without such mitigation they take much longer to happen and release much less radioactive material than earlier analyses suggested. This was borne out at Fukushima, where there was ample time for evacuation – three days – before any significant radioactive releases.

In 2015 the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) released its Study of Consequences of a Hypothetical Severe Nuclear Accident and Effectiveness of Mitigation Measures. This was the result of research and analysis undertaken to address concerns raised during public hearings in 2012 on the environmental assessment for the refurbishment of Ontario Power Generation's (OPG's) Darlington nuclear power plant. The study involved identifying and modelling a large atmospheric release of radionuclides from a hypothetical severe nuclear accident at the four-unit Darlington power plant; estimating the doses to individuals at various distances from the plant, after factoring in protective actions such as evacuation that would be undertaken in response to such an emergency; and, finally, determining human health and environmental consequences due to the resulting radiation exposure. It concluded that there would be no detectable health effects or increase in cancer risk. A fuller write-up of it is on the World Nuclear News website.

A different safety philosophy: early Soviet-designed reactors

The April 1986 disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine was the result of major design deficiencies in the RBMK type of reactor, the violation of operating procedures and the absence of a safety culture. One peculiar feature of the RBMK design was that coolant failure could lead to a strong increase in power output from the fission process (positive void coefficient). However, this was not the prime cause of the Chernobyl accident. It once and for all vindicated the desirability of designing with inherent safety supplemented by robust secondary safety provisions. By way of contrast to western safety engineering, the Chernobyl reactor did not have a containment structure like those used in the West or in post-1980 Soviet designs.

The accident destroyed the reactor, and its burning contents dispersed radionuclides far and wide. This tragically meant that the results were severe, with 56 people killed, 28 of whom died within weeks from radiation exposure. It also caused radiation sickness in a further 200-300 staff and firefighters, and contaminated large areas of Belarus, Ukraine, Russia and beyond. It is estimated that at least 5% of the total radioactive material in the Chernobyl 4 reactor core was released from the plant, due to the lack of any containment structure. Most of this was deposited as dust close by. Some was carried by wind over a wide area.

About 130,000 people received significant radiation doses (i.e. above internationally accepted ICRP limits) and continue to be monitored. According to an UNSCEAR report in 2018, about 20,000 cases of thyroid cancer were diagnosed in 1991-2015 in patients who were 18 and under at the time of the accident. The report states that a quarter of the cases in 2001-2008 were "probably" due to high doses of radiation, and that this fraction was likely to have been higher in earlier years, and lower in later years. However, it also states that the uncertainty around the attributed fraction is very significant – at least 0.07 to 0.5 – and that the influence of annual screenings and active follow-up make comparisons with the general population problematic. Thyroid cancer is usually not fatal if diagnosed and treated early; the report states that of the diagnoses made between 1991 and 2005 (6,848 cases), 15 proved to be fatal. No increase in leukaemia or other cancers have yet shown up, but some is expected. The World Health Organization is closely monitoring most of those affected.

The Chernobyl accident was a unique event and the only time in the history of commercial nuclear power that radiation-related fatalities occurred. The main positive outcome of this accident for the industry was the formation of the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO), building on the US precedent.

The destroyed unit 4 was enclosed in a concrete shelter, which was replaced by a more permanent structure in 2017.

An OECD expert report on the accident concluded: "The Chernobyl accident has not brought to light any new, previously unknown phenomena or safety issues that are not resolved or otherwise covered by current reactor safety programs for commercial power reactors in OECD member countries." In other words, the concept of 'defence in depth' was conspicuous by its absence, and tragically shown to be vitally important.

Apart from the RBMK reactor design, an early Russian PWR design, the VVER-440/V-230, gave rise to concerns in Europe, and a program was initiated to close these down as a condition of EU accession, along with Lithuania’s two RBMK units. See related papers on Early Soviet Reactors and EU Accession, and RBMK Reactors.

However, after the US Atomic Energy Commission published General Design Criteria for Nuclear Power Plants in 1971, Russian PWR designs conformed, according to Rosatom. In particular, the VVER-440/V-213 Loviisa reactors in Finland were designed at that time and modified to conform. The first of these two came on line in 1977.

A broader picture – other past accidents

There have been a number of accidents in experimental reactors and in one military plutonium-producing reactor, including a number of core melts, but none of these has resulted in loss of life outside the actual plant, or long-term environmental contamination. Elsewhere (Safety of Nuclear Power Reactors appendix) we tabulate these, along with the most serious commercial plant accidents. The list of ten probably corresponds to incidents rating level 4 or higher on today’s International Nuclear Event Scale (Table 4). All except Browns Ferry and Vandellos involved damage to or malfunction of the reactor core. At Browns Ferry a fire damaged control cables and resulted in an 18-month shutdown for repairs; at Vandellos a turbine fire made the 17-year old plant uneconomic to repair.

Mention should be made of the accident to the US Fermi 1 prototype fast breeder reactor near Detroit in 1966. Due to a blockage in coolant flow, some of the fuel melted. However no radiation was released offsite and no-one was injured. The reactor was repaired and restarted but closed down in 1972.

The well-publicized criticality accident at Tokai Mura, Japan, in 1999 was at a fuel preparation plant for experimental reactors, and killed two workers from radiation exposure. Many other such criticality accidents have occurred, some fatal, and practically all in military facilities prior to 1980. A review of these is listed in the References section.

In an uncontained reactor accident such as at Windscale (a military facility) in 1957 and at Chernobyl in 1986 (and to some extent Fukushima Daiichi in 2011), the principal health hazard is from the spread of radioactive materials, notably volatile fission products such as iodine-131 and caesium-137. These are biologically active, so that if consumed in food, they tend to stay in organs of the body. I-131 has a half-life of 8 days, so is a hazard for around the first month, (and apparently gave rise to the thyroid cancers after the Chernobyl accident). Caesium-137 has a half-life of 30 years, and is therefore potentially a long-term contaminant of pastures and crops. In addition to these, there is caesium-134 which has a half-life of about two years. While measures can be taken to limit human uptake of I-131, (evacuation of area for several weeks, iodide tablets), high levels of radioactive caesium can preclude food production from affected land for a long time. Other radioactive materials in a reactor core have been shown to be less of a problem because they are either not volatile (strontium, transuranic elements) or not biologically active (tellurium-132, xenon-133).

Accidents in any field of technology provide valuable knowledge enabling incremental improvement in safety beyond the original engineering. Cars and airliners are the most obvious examples of this, but the chemical and oil industries can provide even stronger evidence. Civil nuclear power has greatly improved its safety in both engineering and operation over its 65 years of experience with very few accidents and major incidents to spur that improvement. The Fukushima Daiichi accident was the first since TMI in 1979 which will have significant implications, at least for older plants.

Scrams, seismic shutdowns

A scram is a sudden reactor shutdown. When a reactor is scrammed, automatically due to seismic activity, or due to some malfunction, or manually for whatever reason, the fission reaction generating the main heat stops. However, considerable heat continues to be generated by the radioactive decay of the fission products in the fuel. Initially, for a few minutes, this is great – about 7% of the pre-scram level. But it drops to about 1% of the normal heat output after two hours, to 0.5% after one day, and 0.2% after a week. Even then it must still be cooled, but simply being immersed in a lot of water does most of the job after some time. When the water temperature is below 100°C at atmospheric pressure the reactor is said to be in "cold shutdown".

European 'stress tests' and US response following Fukushima accident

Aspects of nuclear plant safety highlighted by the Fukushima accident were assessed in the nuclear reactors in the EU's member states, as well as those in any neighbouring states that decided to take part. These comprehensive and transparent nuclear risk and safety assessments, the so-called "stress tests", involved targeted reassessment of each power reactor’s safety margins in the light of extreme natural events, such as earthquakes and flooding, as well as on loss of safety functions and severe accident management following any initiating event. They were conducted from June 2011 to April 2012. They mobilized considerable expertise in different countries (500 man-years) under the responsibility of each national Safety Authority within the framework of the European Nuclear Safety Regulators Group (ENSREG).

The Western European Nuclear Regulators' Association (WENRA) proposed these in response to a call from the European Council in March 2011, and developed specifications. WENRA is a network of Chief Regulators of EU countries with nuclear power plants and Switzerland, and has membership from 17 countries. It then negotiated the scope of the tests with the European Nuclear Safety Regulators Group (ENSREG), an independent, authoritative expert body created in 2007 by the European Commission comprising senior officials from the national nuclear safety, radioactive waste safety or radiation protection regulatory authorities from all EU member states, and representatives of the European Commission.

In June 2011 the governments of seven non-EU countries agreed to conduct nuclear reactor stress tests using the EU model. Armenia, Belarus, Croatia, Russia, Switzerland, Turkey and Ukraine signed a declaration that they would conduct stress tests and agreed to peer reviews of the tests by outside experts. Russia had already undertaken extensive checks. (Croatia is co-owner in the Krsko PWR in Slovenia, and Turkey is building its first nuclear plant.)

The reassessment of safety margins is based on the existing safety studies and engineering judgement to evaluate the behaviour of a nuclear power plant when facing a set of challenging situations. For a given plant, the reassessment reports on the most probable behaviour of the plant for each of the situations considered. The results of the reassessment were peer-reviewed and shared among regulators. WENRA noted that it remains a national responsibility to take or order any appropriate measures, such as additional technical or organisational safety provisions, resulting from the reassessment.

The scope of the assessment took into account the issues directly highlighted by the events in Fukushima and the possibility for combination of initiating events. Two 'initiating events' were covered in the scope: earthquake and flooding. The consequences of these – loss of electrical power and station blackout, loss of ultimate heat sink and the combination of both – were analysed, with the conclusions being applicable to other general emergency situations. In accident scenarios, regulators consider power plants' means to protect against and manage loss of core cooling as well as cooling of used fuel in storage. They also study means to protect against and manage loss of containment integrity and core melting, including consequential effects such as hydrogen accumulation.

Nuclear plant operators start by documenting each power plant site. This analysis of 'extreme scenarios' followed what ENSREG called a progressive approach "in which protective measures are sequentially assumed to be defeated" from starting conditions which "represent the most unfavourable operational states." The operators have to explain their means to maintain "the three fundamental safety functions (control of reactivity, fuel cooling confinement of radioactivity)" and support functions for these, "taking into account the probable damage done by the initiating event."

The documents had to cover provisions in the plant design basis for these events and the strength of the plant beyond its design basis. This means the "design margins, diversity, redundancy, structural protection and physical separation of the safety relevant systems, structures and components and the effectiveness of the defence-in-depth concept." This had to focus on 'cliff-edge' effects, e.g. when back-up batteries are exhausted and station blackout is inevitable. For severe accident management scenarios they must identify the time before fuel damage is unavoidable and the time before water begins boiling in used fuel ponds and before fuel damage occurs. Measures to prevent hydrogen explosions and fires are to be part of this.

Since the licensee has the prime responsibility for safety, they performed the reassessments, and the regulatory bodies then independently reviewed them. The exercise covered 147 nuclear plants in 15 EU countries – including Lithuania with only decommissioned plants – plus 15 reactors in Ukraine and five in Switzerland.

Operators reported to their regulators who then reported progress to the European Commission by the end of 2011. Information was shared among regulators throughout this process before the 17 final reports went to peer-review by teams comprising 80 experts appointed by ENSREG and the European Commission. The final documents were published in line with national law and international obligations, subject only to not jeopardising security – an area where each country could behave differently. The process was extended to June 2012 to allow more plant visits and to add more information on the potential effect of aircraft impacts.

The European Commission adopted, with ENSREG, the final stress tests Report on April 26, 2012 and issued the same day a joint statement underlining the quality of the exercise. The full report and a summary of the 45 recommendations were published on www.ensreg.eu. Drawing on the peer reviews, the EC and ENSREG cited four main areas for improving EU nuclear plant safety:

- Guidance from WENRA for assessing natural hazards and margins beyond design basis.

- Giving more importance to periodic safety reviews and evaluation of natural hazards.

- Urgent measures to protect containment integrity.

- Measures to prevent and mitigate accidents resulting from extreme natural hazards.

The results of the stress tests pointed out, in particular, that European nuclear power plants offered a sufficient safety level to require no shutdown of any of them. At the same time, improvements were needed to enhance their robustness to extreme situations. In France, for instance, they were imposed by ASN requirements, which took into account exchanges with its European counterparts. A follow-up European action plan was established by ENSREG from July 2012.

The EU process was completed at the end of September 2012, with the EU Energy Commissioner announcing that the stress tests had showed that the safety of European power reactors was generally satisfactory, but making some other comments and projections which departed from ENSREG. An EC report was presented to the EU Council in October 2012.

In the USA the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in March 2012 made orders for immediate post-Fukushima safety enhancements, with a cost of about $100 million across the whole US fleet. The first order required the addition of equipment at all plants to help respond to the loss of all electrical power and the loss of the ultimate heat sink for cooling, as well as maintaining containment integrity. Another required improved water level and temperature instrumentation on used fuel ponds. The third order applied only to the 33 BWRs with early containment designs, and required 'reliable hardened containment vents' which work under any circumstances. The US industry association, the Nuclear Energy Institute, told the NRC that licensees with these Mark I and Mark II containments “should have the capability to use various filtration strategies to mitigate radiological releases” during severe events, and that filtration “should be founded on scientific and factual analysis and should be performance-based to achieve the desired outcome.” All the measures are supported by the industry association, which also proposed setting up about six regional emergency response centres under NRC oversight with additional portable equipment.

In Japan similar stress tests were carried out in 2011 under the previous safety regulator, but then reactor restarts were delayed until the newly constituted Nuclear Regulatory Authority devised and published new safety guidelines, then applied them progressively through the fleet.

Earthquakes and volcanoes

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has a Safety Guide on Seismic Risks for Nuclear Power Plants, and the matter is dealt with in the WNA page on Earthquakes and Nuclear Power Plants. Volcanic hazards are minimal for practically all nuclear plants, but the IAEA has developed a new Safety Guide on the matter. The Bataan plant in Philippines which has never operated, and the Armenian plant at Metsamor are two known to be in proximity to potential volcanic activity.

Flooding – storms, tides and tsunamis

Nuclear plants are usually built close to water bodies, for the sake of cooling. The site licence takes account of worst case flooding scenarios as well as other possible natural disasters and, more recently, the possible effects of climate change. As a result, all the buildings with safety-related equipment are situated on high enough platforms so that they stand above submerged areas in case of flooding events. As an example, French Safety Rules criteria for river sites define the safe level as above a flood level likely to be reached with one chance in one thousand years, plus 15%, and similar regarding tides for coastal sites.

Occasionally in the past some buildings have been sited too low, so that they are vulnerable to flood or tidal and storm surge, so engineered countermeasures have been built. EDF's Blayais nuclear plant in western France uses seawater for cooling and the plant itself is protected from storm surge by dykes. However, in 1999 a 2.5 m storm surge in the estuary overtopped the dykes – which were already identified as a weak point and scheduled for a later upgrade – and flooded one pumping station. For security reasons it was decided to shut down the three reactors then under power (the fourth was already stopped in the course of normal maintenance). This incident was rated 2 on the INES scale.

In 1994 the Kakrapar nuclear power plant near the west coast of India was flooded due to heavy rains together with failure of weir control for an adjoining water pond, inundating turbine building basement equipment. The back-up diesel generators on site enabled core cooling using fire water, a backup to process water, since the offsite power supply failed. Following this, multiple flood barriers were provided at all entry points, inlet openings below design flood level were sealed and emergency operating procedures were updated. In December 2004 the Madras NPP and Kalpakkam PFBR site on the east coast of India was flooded by a tsunami surge from Sumatra. Construction of the Kalpakkam plant was just beginning, but the Madras plant shut down safely and maintained cooling. However, recommendations including early warning system for tsunami and provision of additional cooling water sources for longer duration cooling were implemented.

In March 2011 the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant was affected seriously by a huge tsunami induced by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Three of the six reactors were operating at the time, and had shut down automatically due to the earthquake. The back-up diesel generators for those three units were then swamped by the tsunami. This cut power supply and led to weeks of drama and loss of the reactors. The design basis tsunami height was 5.7 m for Daiichi (and 5.2 m for adjacent Daini, which was actually set a bit higher above sea level). Tsunami heights coming ashore were about 14 metres for both plants. Unit 3 of Daini was undamaged and continued to cold shutdown status, but the other units suffered flooding to pump rooms where equipment transfers heat from the reactor circuit to the sea – the ultimate heat sink.

The maximum amplitude of this tsunami was 23 metres at point of origin, about 160 km from Fukushima. In the last century there had been eight tsunamis in the Japan region with maximum amplitudes above 10 metres (some much more), these having arisen from earthquakes of magnitude 7.7 to 8.4, on average one every 12 years. Those in 1983 and in 1993 were the most recent affecting Japan, with maximum heights 14.5 metres and 31 metres respectively, both induced by magnitude 7.7 earthquakes. This 2011 earthquake was magnitude 9.

For low-lying sites, civil engineering and other measures are normally taken to make nuclear plants resistant to flooding. Lessons from Blayais and Fukushima have fed into regulatory criteria. Sea walls have been and are being built or increased at Hamaoka, Shimane, Mihama, Ohi, Takahama, Onagawa, and Higashidori plants. However, few parts of the world have the same tsunami potential as Japan, and for the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of Europe the maximum amplitude is much less than Japan.

Hydrogen

In any light-water nuclear power reactor, hydrogen is formed by radiolytic decomposition of water. This needs to be dealt with to avoid the potential for explosion with oxygen present, and many reactors have been retrofitted with passive autocatalytic hydrogen recombiners in their containment, replacing external recombiners that needed to be connected and powered, isolated behind radiological barriers. Also in some kinds of reactor, particularly early boiling water types, the containment is rendered inert by injection of nitrogen.

In an accident situation such as at Fukushima where the fuel became very hot, a lot of hydrogen is formed by the oxidation of zirconium fuel cladding in steam at about 1300°C. This is beyond the capability of the normal hydrogen recombiners to deal with, and operators must rely on venting to atmosphere or inerting the containment with nitrogen.

International collaboration to improve safety

There is a lot of international collaboration, but it has evolved from the bottom, and only in 1990s has there been any real top-down initiative. In the aviation industry the Chicago Convention in the late 1940s initiated an international approach which brought about a high degree of design collaboration between countries, and the rapid universal uptake of lessons from accidents. There are cultural and political reasons for this which mean that even the much higher international safety collaboration since the 1990s is still less than in aviation. See also paper on Cooperation in Nuclear Power Industry, especially for fuller description of WANO, focused on operation.

World Association of Nuclear Operators

International cooperation on nuclear safety issues takes place under the auspices of the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO) which was set up in 1989. In practical terms this is the most effective international means of achieving very high levels of safety through its four major programs: peer reviews; operating experience; technical support and exchange; and professional and technical development. WANO peer reviews are the main proactive way of sharing experience and expertise, and by the end of 2009 every one of the world's commercial nuclear power plants had been peer-reviewed at least once. Following the Fukushima accident these have been stepped up to one every four years at each plant, with follow-up visits in between, and the scope extended from operational safety to include plant design upgrades. Pre-startup reviews of new plants are being increased.

IAEA Convention on Nuclear Safety

The IAEA Convention on Nuclear Safety (CNS) was drawn up during a series of expert level meetings from 1992 to 1994 and was the result of considerable work by Governments, national nuclear safety authorities and the IAEA Secretariat. Its aim is to legally commit participating States operating land-based nuclear power plants to maintain a high level of safety by setting international benchmarks to which States would subscribe.

The obligations of the Parties are based to a large extent on the principles contained in the IAEA Safety Fundamentals document The Safety of Nuclear Installations. These obligations cover for instance, siting, design, construction, operation, the availability of adequate financial and human resources, the assessment and verification of safety, quality assurance and emergency preparedness.

The Convention is an incentive instrument. It is not designed to ensure fulfilment of obligations by Parties through control and sanction, but is based on their common interest to achieve higher levels of safety. These levels are defined by international benchmarks developed and promoted through regular meetings of the Parties. The Convention obliges Parties to report on the implementation of their obligations for international peer review. This mechanism is the main innovative and dynamic element of the Convention. Under the Operational Safety Review Team (OSART) program dating from 1982 international teams of experts conduct in-depth reviews of operational safety performance at a nuclear power plant. They review emergency planning, safety culture, radiation protection, and other areas. OSART missions are on request from the government, and involve staff from regulators, in these respects differing from WANO peer reviews.

The Convention entered into force in October 1996. As of March 2021, there were 91 signatories to the Convention, 65 of which are contracting parties, including all countries with operating nuclear power plants.

The IAEA General Conference in September 2011 unanimously endorsed the Action Plan on Nuclear Safety that Ministers requested in June. The plan arose from intensive consultations with Member States but not with industry, and was described as both a rallying point and a blueprint for strengthening nuclear safety worldwide. It contains suggestions to make nuclear safety more robust and effective than before, without removing the responsibility from national bodies and governments. It aims to ensure "adequate responses based on scientific knowledge and full transparency". Apart from strengthened and more frequent IAEA peer reviews (including those of regulatory systems), most of the 12 recommended actions are to be undertaken by individual countries and are likely to be well in hand already.

Following this, an extraordinary general meeting of 64 of the CNS parties in September 2012 gave a strong push to international collaboration in improving safety. National reports at future three-yearly CNS review meetings will cover a list of specific design, operational and organizational issues stemming from Fukushima lessons. They include further design features to avoid long-term offsite contamination and enhancement of emergency preparedness and response measures, including better definition of national responsibilities and improved international cooperation. Parties should also report on measures to "ensure the effective independence of the regulatory body from undue influence."

In February 2015 diplomats from 72 countries unanimously adopted the Vienna Declaration of Nuclear Safety, setting out “principles to guide them, as appropriate, in the implementation of the objective of the CNS to prevent accidents with radiological consequences and mitigate such consequences should they occur” but rejected Swiss amendments to the CNS as impractical. However, in line with Swiss and EU intentions, "comprehensive and systematic safety assessments are to be carried out periodically and regularly for existing installations throughout their lifetime in order to identify safety improvements... Reasonably practicable or achievable safety improvements are to be implemented in a timely manner."

IAEA design safety reviews and generic reactor safety reviews

An IAEA design safety review (DSR) is performed at the request of a member state organization to evaluate the completeness and comprehensiveness of a reactor's safety documentation by an international team of senior experts. It is based on IAEA published safety requirements. If the DSR is for a vendor’s design at the pre-licensing stage, it is done using the generic reactor safety review (GRSR) module. IAEA Safety Standards, applied in the DSR and GRSR at the fundamental and requirements level, are generic and apply to all nuclear installations. Therefore, it is neither intended nor possible to cover or substitute licensing activity, or to constitute any kind of design certification.

DSRs have been undertaken in Armenia (2003, 2009), Bangladesh (2018), Bulgaria (2008), Pakistan (2006) and Ukraine (2008, 2009). GRSRs have been carried out on ACP100, ACP1000, ACPR-1000+, ACR1000, AES-2006, AP1000 (USA & UK), APR1000, APR1400, Atmea1, CAP1400, EPR, ESBWR, and VVER-TOI.

Eastern Europe from 1980s

In relation to Eastern Europe particularly, since the late 1980s a major international program of assistance was carried out by the OECD, IAEA and Commission of the European Communities to bring early Soviet-designed reactors up to near western safety standards, or at least to effect significant improvements to the plants and their operation. The European Union also brought pressure to bear, particularly in countries which aspired to EU membership.

Modifications were made to overcome deficiencies in the 11 RBMK reactors still operating at the time in Russia. Among other things, these removed the danger of a positive void coefficient response. Automated inspection equipment has also been installed in these reactors.

The other class of reactors which has been the focus of international attention for safety upgrades is the first-generation of pressurised water VVER-440 reactors. The V-230 model was designed before formal safety standards were issued in the Soviet Union and they lack many basic safety features. Two are still operating in Russia and one in Armenia, under close inspection.

Later Soviet-designed reactors are very much safer and have Western control systems or the equivalent, along with containment structures.

Europe since 1999

The main European safety collaboration is through the European Nuclear Safety Regulators Group (ENSREG), an independent, authoritative expert body created in 2007 by the European Commission to revive the EU nuclear safety directive, which was passed in June 2009. It comprises senior officials from the national nuclear safety, radioactive waste safety or radiation protection regulatory authorities from all 27 EU member states, and representatives of the European Commission. It was preceded in 1999 by the Western European Nuclear Regulators' Association (WENRA), a network of Chief Regulators of EU countries with nuclear power plants and Switzerland, with membership from 17 countries.

Ageing of nuclear plants; knowledge management

Engineering

Several issues arise in prolonging the lives of nuclear plants which were originally designed for nominal 30- or 40-year operating lives. Systems, structures and components (SSC) whose characteristics change gradually with time or use are the subject of attention, which is applied with vastly greater scientific and technical knowledge than that available to the original designers many decades ago.

Some components simply wear out, corrode or degrade to a low level of efficiency. These need to be replaced. Steam generators are the most prominent and expensive of these, and many have been replaced after about 30 years where the reactor otherwise has the prospect of running for 60 years. This is essentially an economic decision. Lesser components are more straightforward to replace as they age, and some may be safety-related as well as economic.

In PHWR units, notably CANDU reactors, pressure tube replacement has been undertaken on some older plants, after some 30 years of operation. Fuel channel integrity is another limiting factor for Candu reactors, and mid-life inspection and analysis can extend the original 175,000 full-power operating hours design assumption to 300,000 hours.

A second issue is that of obsolescence. For instance, older reactors have analogue instrument and control systems, and a question must be faced regarding whether these are replaced with digital in a major mid-life overhaul, or simply maintained.

Thirdly, the properties of materials may degrade with age, particularly with heat and neutron irradiation. In some early Russian pressurized water reactors, the pressure vessel is relatively narrow and is thus subject to greater neutron bombardment that a wider one. This raises questions of embrittlement, and has had to be checked carefully before extending licences.

In some Russian and UK plants (RBMK, AGR), graphite is used as the moderator. The graphite blocks cannot be replaced during the operating life of the reactors. However, radiation damage changes the shape and size of the crystallites that comprise graphite, giving some dimensional change and degradation of the structural properties of the graphite. For continued operation, it is therefore necessary to demonstrate that the graphite can still perform its intended role irrespective of the degradation, or undergo some repair. In Russia, after dismantling the pressure tubes, longitudinal cutting of a limited number of deformed graphite columns returns the graphite stack geometry to a condition that meets the initial design requirements. Leningrad 1 was the first RBMK reactor to undergo this over 2012-13.

In respect to all these aspects, periodic safety reviews are undertaken on most older plants in line with the IAEA safety convention and WANO's safety culture principles to ensure that safety margins are maintained. The IAEA undertakes Safety Aspects of Long-Term Operation (SALTO) evaluations of reactors on request from member countries. These SALTO missions check both physical and organizational aspects, and function as an international peer review of the national regulator. They are backed up by the IAEA International Generic Ageing Lessons Learned (IGALL) program which is documented in databases and publications, in the form of downloadable safety guides and reports on ageing.

Equipment performance is constantly monitored to identify faults and failures of components. Preventative maintenance is adapted and scheduled in the light of this, to ensure that the overall availability of systems important for both safety and plant availability are within the design basis, or better than the original design basis. Collecting reliability and performance data is of the utmost importance, as well as analysing them, for tracking indicators that might be signs of ageing, or indicative of potential problems having been under-estimated, or of new problems. The results of this monitoring and analysis are often shared Industry-wide through INPO and WANO networks. The use of probabilistic safety analysis makes possible risk-informed decisions regarding maintenance and monitoring programs, so that adequate attention is given to the health of every piece of equipment in the plant. This process is similar to that in other industries where safety is paramount, e.g. aviation. Reliability centred maintenance was adapted from civil aviation in the 1980s for instance, and led to nuclear industry review of existing maintenance programmes.

In the USA most of the about 95 reactors are expected to be granted operating licence extensions from 40 to 60 years, with many to 80 years. This justifies significant capital expenditure in upgrading systems and components, including building in extra performance margins.

Knowledge management

The IAEA has a safety knowledge base for ageing and long-term operation of nuclear power plants (SKALTO) which aims to develop a framework for sharing information on ageing management and long term operation of nuclear power plants. It provides published documents and information related to this.

Knowledge management in relation to the original design basis of reactors becomes an issue with corporate reorganisation or demise of vendors, coupled with changes made over several decades. While operators usually have good records, some regulators do not. Design Basis Knowledge Management (DKM) is an issue receiving a lot of attention in the last ten years or so.

Nuclear DKM addresses the specific needs of nuclear plants and organizations. Its scope extends from research and development, through design and engineering, construction, commissioning, operations, maintenance, refurbishment and long-term operation (LTO), waste management, to decommissioning. Nuclear DKM issues and priorities are often unique to the particular circumstances of individual countries and their regulators as well as other nuclear industry organizations. Nuclear DKM may focus on knowledge creation, identification, sharing, transfer, protection, validation, storage, dissemination, preservation or utilization. Nuclear DKM practices may enhance and support traditional business functions and goals such as human resource management, training, planning, operations, maintenance, and much more.

There must always be a responsible owner of the DKM system for any plant. In most cases this will be the operator, however, based on a variety of changes such as market conditions, the responsible owner may change over time. An effective nuclear DKM system should be focused on strengthening and aligning the knowledge base in three primary knowledge domains in an organization: people, processes and technology, each of which must also be considered within the context of the organizational culture. Knowledge management policies and practices should help create a supportive organizational culture that recognizes the value of nuclear knowledge and promotes effective processes to maintain it.

In Canada, the Pickering A – Bruce A saga is a cautionary tale (and classic industry case study) regarding DKM. By the mid-1990s there was a divergence between drawings and modifications which had progressively been made, and also the operating company had not shared operating experience with the designer. Maintenance standards fell and costs rose. A detailed audit in 1997-98 showed that the design basis was not being maintained and that 4000 additional staff would be required to correct the situation at all Ontario Hydro plants, so the two A plants (eight units) were shut down so that staff could focus on the 12 units not needing so much attention. From 2003, six of the eight A units were returned to service with design basis corrected, having been shut down for several years – a significant loss of asset base for the owners.

Reporting nuclear incidents

The International Nuclear Event Scale (INES) was developed by the IAEA and OECD in 1990 to communicate and standardise the reporting of nuclear incidents or accidents to the public. The scale runs from a zero event with no safety significance to 7 for a "major accident" such as Chernobyl. TMI rated 5, as an "accident with off-site risks" though no harm to anyone, and a level 4 "accident mainly in installation" occurred in France in 1980, with little drama. Another accident rated at level 4 occurred in a fuel processing plant in Japan in September 1999. Other accidents have been in military plants .

The International Nuclear Event Scale

For prompt communication of safety significance

| Level, Descriptor |

Off-Site Impact, release of radioactive materials |

On-Site Impact |

Defence-in-Depth Degradation |

Examples |

7

Major Accident |

Major Release:

Widespread health and environmental effects |

|

|

Chernobyl, Ukraine, 1986 (fuel meltdown and fire);

Fukushima Daiichi 1-3, 2011 (fuel damage, radiation release and evacuation) |

6

Serious Accident |

Significant Release:

Full implementation of local emergency plans |

|

|

Mayak at Ozersk, Russia, 1957 'Kyshtym' (reprocessing plant criticality) |

5

Accident with Off-Site Consequences |

Limited Release:

Partial implementation of local emergency plans, or |

Severe damage to reactor core or to radiological barriers |

|

Three Mile Island, USA, 1979 (fuel melting);

Windscale, UK, 1957 (military)

|

4

Accident Mainly in Installation, with local consequences.

either of: |

Minor Release:

Public exposure of the order of prescribed limits, or |

Significant damage to reactor core or to radiological barriers; worker fatality |

|

Saint-Laurent A1, France, 1969 (fuel rupture) & A2 1980 (graphite overheating);

Tokai-mura, Japan, 1999 (criticality in fuel plant for an experimental reactor). |

3

Serious Incident

any of: |

Very Small Release:

Public exposure at a fraction of prescribed limits, or |

Major contamination; Acute health effects to a worker, or |

Near Accident:

Loss of Defence in Depth provisions - no safety layers remaining |

Fukushima Daiichi 4, 2011 (fuel pond overheating);

Fukushima Daini 1, 2, 4, 2011 (interruption to cooling);

Vandellos, Spain, 1989 (turbine fire);

Davis-Besse, USA, 2002 (severe corrosion);

Paks, Hungary 2003 (fuel damage) |

2

Incident |

nil |

Significant spread of contamination; Overexposure of worker, or |

Incidents with significant failures in safety provisions |

|

1

Anomaly |

nil |

nil |

Anomaly beyond authorised operating regime |

|

0

Deviation |

nil |

nil |

No safety significance |

|

| Below Scale |

nil |

nil |

No safety relevance |

|

Source: International Atomic Energy Agency

Security – terrorism, etc.

See also information page on Nuclear Security of Nuclear Facilities and Material.

Since the World Trade Centre attacks in New York in 2001 there has been increased concern about the consequences of a large aircraft being used to attack a nuclear facility with the purpose of releasing radioactive materials. Various studies have looked at similar attacks on nuclear power plants. They show that nuclear reactors would be more resistant to such attacks than virtually any other civil installations – see Appendix. A thorough study was undertaken by the US Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) using specialist consultants and paid for by the US Dept. of Energy. It concludes that US reactor structures "are robust and (would) protect the fuel from impacts of large commercial aircraft".

The analyses used a fully-fuelled Boeing 767-400 of over 200 tonnes as the basis, at 560 km/h – the maximum speed for precision flying near the ground. The wingspan is greater than the diameter of reactor containment buildings and the 4.3 tonne engines are 15 metres apart. Hence analyses focused on single engine direct impact on the centreline – since this would be the most penetrating missile – and on the impact of the entire aircraft if the fuselage hit the centreline (in which case the engines would ricochet off the sides). In each case no part of the aircraft or its fuel would penetrate the containment. Other studies have confirmed these findings.

Penetrating (even relatively weak) reinforced concrete requires multiple hits by high speed artillery shells or specially-designed "bunker busting" ordnance – both of which are well beyond what terrorists are likely to deploy. Thin-walled, slow-moving, hollow aluminium aircraft, hitting containment-grade heavily-reinforced concrete disintegrate, with negligible penetration. But further (see Sept 2002 Science paper and Jan 2003 Response & Comments), realistic assessments from decades of analyses, lab work and testing, find that the consequence of even the worst realistic scenarios – core melting and containment failure – can cause few if any deaths to the public, regardless of the scenario that led to the core melt and containment failure. This conclusion was documented in a 1981 EPRI study, reported and widely circulated in many languages, by Levenson and Rahn in Nuclear Technology.

In 1988 Sandia National Laboratories in USA demonstrated the unequal distribution of energy absorption that occurs when an aircraft impacts a massive, hardened target. The test involved a rocket-propelled F4 Phantom jet (about 27 tonnes, with both engines close together in the fuselage) hitting a 3.7m thick slab of concrete at 765 km/h. This was to see whether a proposed Japanese nuclear power plant could withstand the impact of a heavy aircraft. It showed how most of the collision energy goes into the destruction of the aircraft itself – about 96% of the aircraft's kinetic energy went into the its destruction and some penetration of the concrete – while the remaining 4% was dissipated in accelerating the 700-tonne slab. The maximum penetration of the concrete in this experiment was 60 mm, but comparison with fixed reactor containment needs to take account of the 4% of energy transmitted to the slab. See also video clip.

As long ago as the late 1970s, the UK Central Electricity Generating Board considered the possibility of a fully-laden and fully-fuelled large passenger aircraft being hijacked and deliberately crashed into a nuclear reactor. The main conclusions were that an airliner would tend to break up as it hit various buildings such as the reactor hall, and that those pieces would have little effect on the concrete biological shield surrounding the reactor. Any kerosene fire would also have little effect on that shield. In the 1980s in the USA, at least some plants were designed to take a hit from a fully-laden large military transport aircraft and still be able to achieve and maintain cold shutdown.

The study of a 1970s US power plant in a highly-populated area is assessing the possible effects of a successful terrorist attack which causes both meltdown of the core and a large breach in the containment structure – both extremely unlikely. It shows that a large fraction of the most hazardous radioactive isotopes, like those of iodine and tellurium, would never leave the site.

Much of the radioactive material would stick to surfaces inside the containment or becomes soluble salts that remain in the damaged containment building. Some radioactive material would nonetheless enter the environment some hours after the attack in this extreme scenario and affect areas up to several kilometres away. The extent and timing of this means that with walking-pace evacuation inside this radius it would not be a major health risk. However it could leave areas contaminated and hence displace people in the same way as a natural disaster, giving rise to economic rather than health consequences.

Looking at spent fuel storage pools, similar analyses showed no breach. Dry storage and transport casks retained their integrity. "There would be no release of radionuclides to the environment".

Similarly, the massive structures mean that any terrorist attack even inside a plant (which are well defended) and causing loss of cooling, core melting and breach of containment would not result in any significant radioactive releases.

However, while the main structures are robust, the 2001 attacks did lead to increased security requirements and plants were required by NRC to install barriers, bulletproof security stations and other physical modifications which in the USA are estimated by the industry association to have cost some $2 billion across the country.

See also Science magazine article 2002 and Appendix.

Switzerland's Nuclear Safety Inspectorate studied a similar scenario and reported in 2003 that the danger of any radiation release from such a crash would be low for the older plants and extremely low for the newer ones.

The conservative design criteria which caused most power reactors to be shrouded by massive containment structures with biological shield has provided peace of mind in a suicide terrorist context. Ironically and as noted earlier, with better understanding of what happens in a core melt accident inside, they are now seen to be not nearly as necessary in that accident mitigation role as was originally assumed.

Advanced reactor designs

The designs for nuclear plants being developed for implementation in coming decades contain numerous safety improvements based on operational experience. The first two of these advanced reactors began operating in Japan in 1996.

One major feature they have in common (beyond safety engineering already standard in Western reactors) is passive safety systems, requiring no operator intervention in the event of a major malfunction.